by Connor Darrell, Head of Investments

The stock market continued to brush off the ever-growing list of political headlines on its way to another positive week. The S&P 500 climbed 0.88%, while international stocks bounced back from a turbulent month, posting strong gains as well. Last week also brought further flattening of the yield curve, with the yield on the 30-Year Treasury dropping below 3%.

On Wednesday 8/22, the current bull market officially became the longest on record, which prompted a litany of columns and conversations dedicated to trying to hypothesize when it will finally come to an end. However, the age of a bull market really has no predictive value in determining whether or not it can endure, and we continue to instruct clients to focus on the core foundations of the economy (including the “heat map”), which continue to suggest that a general aura of optimism is justified.

It Still Makes Sense to be Globally Diversified

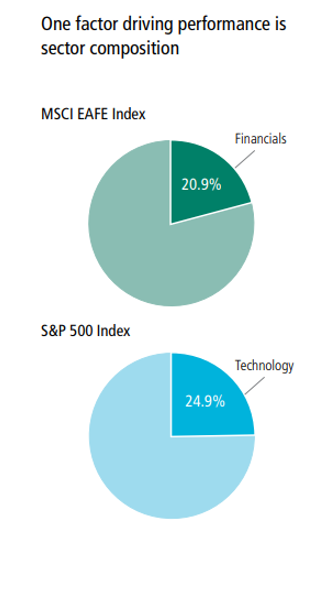

It is no secret that international equities have underperformed their U.S. counterparts in 2018, and the volatility has caused some investors to question the merits of holding a globally diversified equity portfolio. While much of the uncertainty has been due to a weakening macro backdrop in Europe (as well as the currency crisis in Turkey), it should be noted that sector concentrations have also played a part.  The S&P 500 has been bolstered by the performance of fast growing technology stocks, which have outperformed by a substantial margin in comparison to the overall market. The MSCI EAFE (a commonly followed benchmark of international stocks) on the other hand, has not benefitted from the same tailwinds due to its different sector/industry weightings (see chart right).

The S&P 500 has been bolstered by the performance of fast growing technology stocks, which have outperformed by a substantial margin in comparison to the overall market. The MSCI EAFE (a commonly followed benchmark of international stocks) on the other hand, has not benefitted from the same tailwinds due to its different sector/industry weightings (see chart right).

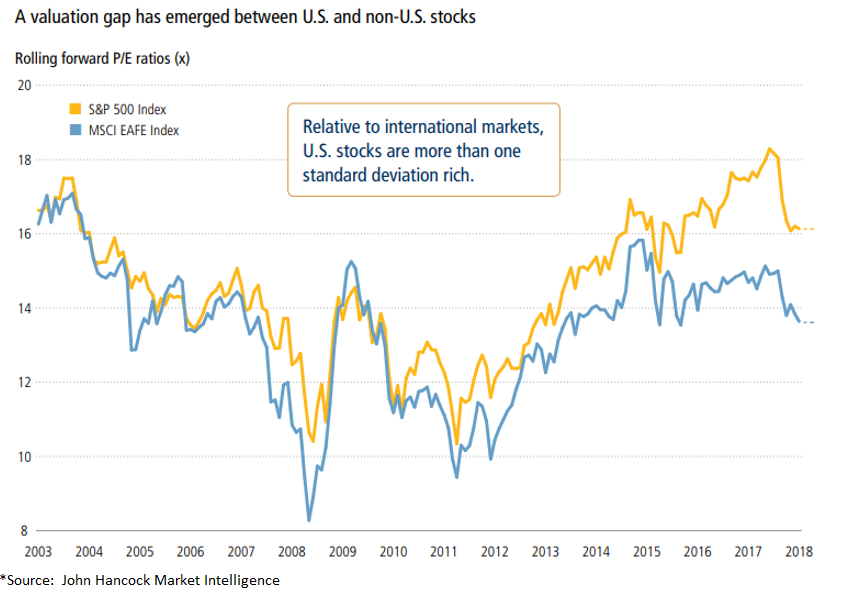

As this has played out over the past several years, the valuation “gap” between U.S. and international equities has expanded to its widest margin in more than 15 years (see chart below).

Valuations are a notoriously ineffective market timing mechanism but have been historically very helpful in predicting long-term variations in relative performance across markets. It will be interesting to watch this dynamic moving forward, as the U.S. inches closer and closer to the theoretical “inflection point”, where monetary policy tightens enough to become a meaningful headwind to market expansion. Internationally, Central Banks are significantly behind in their tightening cycles, and are only just beginning to contemplate adjusting the “easy money” policies of the last decade.