by Connor Darrell, Head of Investments

CLICK HERE TO GET TO KNOW CONNOR

After a rough start to spring, the market seemed to turn a corner during the middle of last week, when on Wednesday equities opened sharply lower but came roaring back to close the day in the black. However, more disruptive trade talk on Friday erased all of the week’s gains. The Department of Labor also released its March jobs report on Friday, but anyone looking for an encore to February’s blockbuster report to provide some respite was left disappointed. The economy continued to add new jobs, but the rate of growth (103,000 new jobs) came in below expectations.

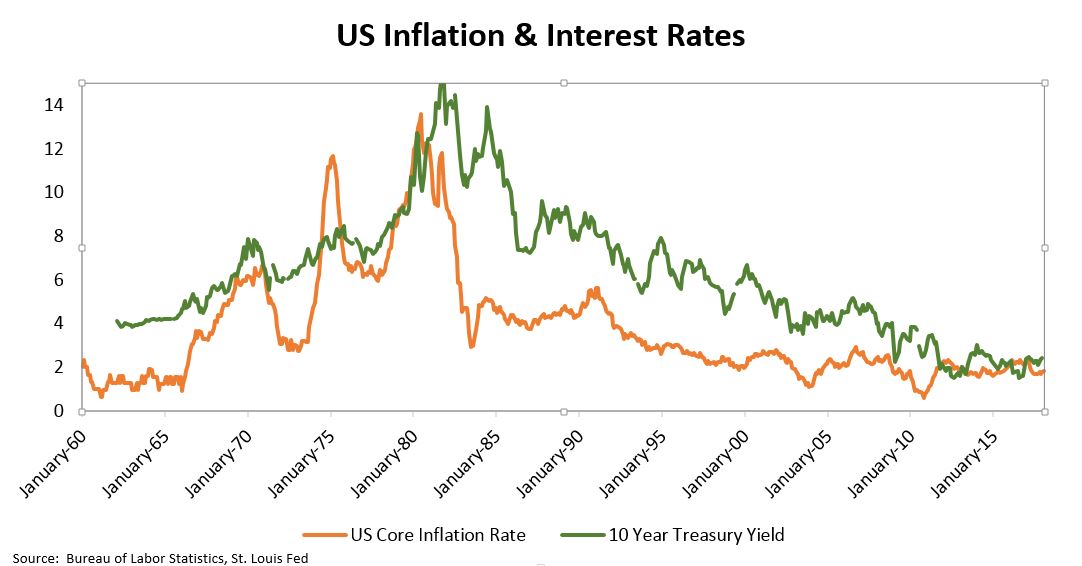

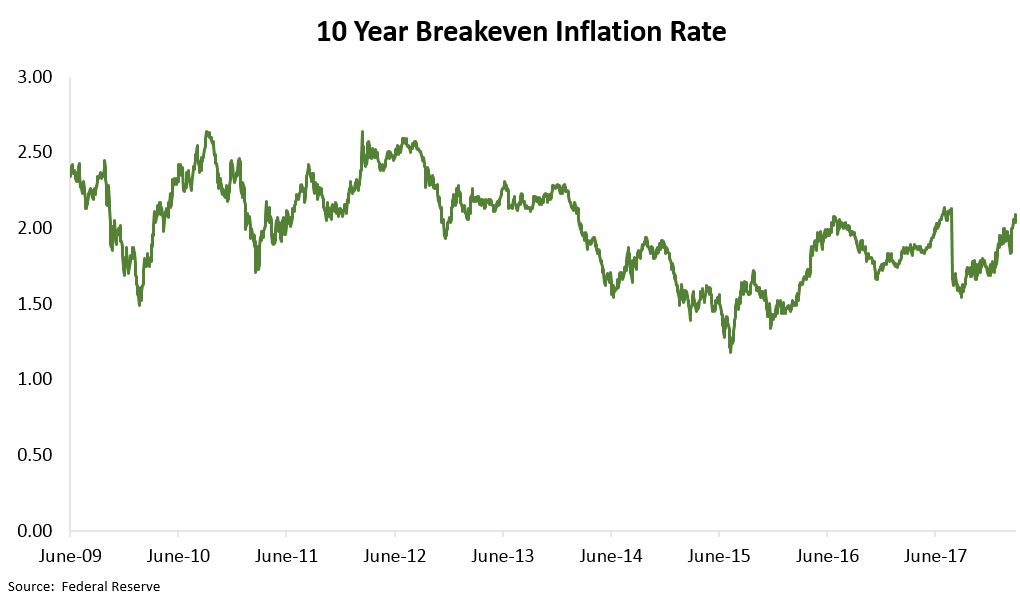

For equity investors, the transition from 2017 to 2018 has not been easy to stomach. Volatility has become the new norm, and news headlines that would have been shrugged off a year ago are now sending shockwaves throughout investors’ portfolios. We expect this trend of increased volatility to continue as markets come to terms with a much wider range of factors to consider. Monetary and fiscal policies are now pushing in opposite directions (the Federal Reserve’s policy of raising interest rates is considered to be contractionary, while tax cuts are considered to be expansionary), and rising trade tensions have added a new dynamic to the equation. All of this is occurring as we are yet another year further along in the economic cycle.

Volatility: Where Economics and Psychology Meet

Periods of heightened volatility are uncomfortable, but provide an excellent opportunity to reflect upon the psychological aspects of investing. When markets are firing on all cylinders, it can be awfully easy to forget that investing involves risk. Ech and every one of us has a different level of tolerance for how much risk we are willing to accept, but often times we don’t know our true tolerance until we experience real volatility. If you find yourself losing sleep over the ebbs and flows of the equity market, then that probably means your portfolio is too aggressive. In many ways, the best portfolio allocation is not the one that maximizes your return, but the one that best aligns with your financial goals and risk tolerance.

Morningstar, a well-respected voice in the investment community, released a study back in 2017 that explored why the average portfolio has struggled to keep pace with the overall market. Their conclusion was that many investors try to time the markets, a notoriously difficult (if not, impossible) thing to successfully implement on a consistent basis. Not only is this approach typically unsuccessful, but it also adds transaction costs and can be very inefficient from a tax standpoint. Over the long term, the best portfolio strategy is the one that enables you to remain disciplined and “in the game.” Sometimes that means building a portfolio that may not keep pace with every bull market, but will provide you with peace of mind when the going gets tough. The ability to match your portfolio with your goals and risk tolerance, in addition to their role as a behavioral “coach” during periods of market stress, are two of the most significant benefits of working with an advisor that is familiar with your unique situation.